Creatine Beyond the Gym: What Practitioners Should Know About the Phosphagen System

Creatine is one of the most researched compounds in sports nutrition and still one of the most misunderstood in clinical practice.

For many practitioners, creatine sits awkwardly in the “sports supplement” category: useful for power athletes, bodybuilders, or short-burst performance, but not obviously relevant to everyday clients, clinical populations, or fatigue-driven presentations.

That framing misses the bigger picture.

Creatine is not simply a performance aid. It is a core component of cellular energy regulation, with relevance far beyond the gym floor. Understanding how creatine works and where it fits within the phosphagen system allows practitioners to apply it more thoughtfully across fatigue, recovery, ageing, neurological demand, and repeated stress exposure.

This article explores creatine from a clinical and physiological lens, not a marketing one.

Creatine and the Phosphagen System: A Quick Refresher

To understand creatine, we need to revisit the phosphagen (ATP–PC) system, the body’s most immediate energy system.

The phosphagen system exists to solve a simple but critical problem:

ATP is required instantly, but ATP stores are limited.

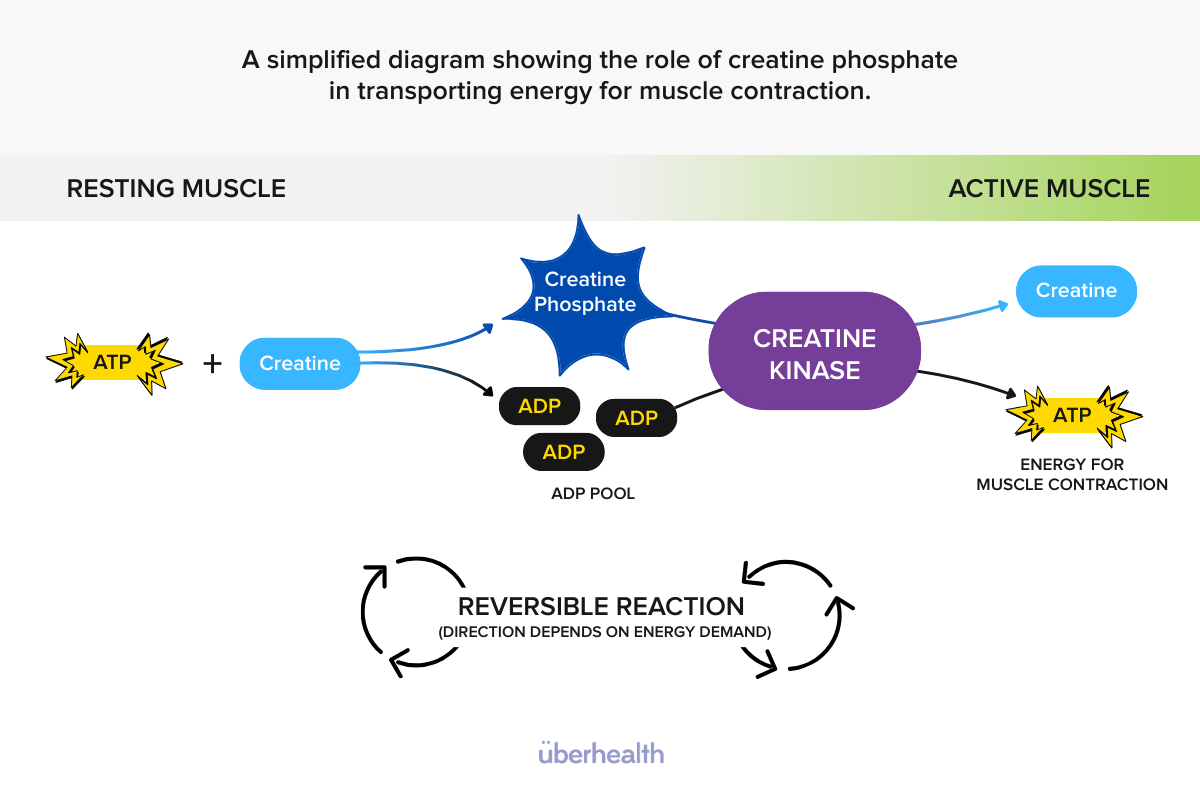

Creatine acts as an energy buffer by storing high-energy phosphate groups in the form of creatine phosphate (phosphocreatine). When energy demand spikes — whether through physical effort, neurological demand, or cellular stress — creatine phosphate donates its phosphate to ADP to rapidly regenerate ATP.

This reaction:

- Happens in seconds

- Requires no oxygen

- Is reversible

- Is catalysed by creatine kinase

In other words, creatine does not “create energy”, it stabilises energy availability when demand outpaces supply. That distinction matters clinically.

Creatine Stores, Turnover, and Daily Demand

Creatine is not a static compound. It is continuously:

- Synthesised endogenously (primarily in the liver and kidneys)

- Obtained through dietary intake (mainly animal proteins)

- Transported into tissues with high energy demand

- Degraded and excreted at a predictable daily rate

Where creatine is stored

Approximately:

- 95% of creatine is stored in skeletal muscle

- The remainder is distributed across the brain, heart, and other metabolically active tissues

These tissues all share one feature: high, fluctuating energy demand.

Daily turnover

Roughly 1–2% of total body creatine is degraded daily and must be replaced through:

- Endogenous synthesis

- Dietary intake

- Supplementation (when appropriate)

This means creatine availability reflects long-term balance, not just acute intake.

Creatine Depletion: More Common Than We Think

Creatine deficiency doesn’t present as a single, obvious symptom. Instead, it tends to show up as reduced energy resilience a.k.a the inability to respond efficiently to repeated or sudden demands.

Groups more likely to have lower creatine availability include:

1. Plant-based or low-animal-protein diets

Creatine is found almost exclusively in animal foods. Individuals following vegetarian or vegan diets rely entirely on endogenous synthesis, which may not fully compensate under higher demand.

2. Women - particularly during perimenopause and menopause

Hormonal shifts influence muscle mass, mitochondrial efficiency, and phosphocreatine storage. Women are historically underrepresented in creatine research, yet may have more to gain in terms of strength, recovery, and fatigue buffering.

3. Ageing populations

Creatine stores decline with age, alongside:

- Muscle mass

- Neuromuscular efficiency

- Recovery capacity

This has implications not just for strength, but for fall risk, functional capacity, and cognitive resilience.

4. Individuals under chronic cognitive or emotional load

Creatine is not muscle-exclusive. The brain uses creatine to stabilise ATP during:

- Sustained focus

- Stress response

- Sleep disruption

- High cognitive demand

Fatigue here is often labelled “adrenal” or “burnout”, when it may be partially energetic.

5. Clients exposed to repeated high-intensity stress

This includes not only athletes, but:

- Shift workers

- Emergency responders

- Busy professionals juggling training, work, and family

- Clients who “cope” well… until they don’t

Creatine, Fatigue, and Recovery: The Clinical Intersection

One of the most useful ways to reframe creatine is this: Creatine supports rate of recovery, not just performance output.

Creatine does not replace aerobic metabolism. It does not override mitochondrial function. Instead, it:

- Buffers ATP during spikes in demand

- Reduces reliance on rapid glycolysis

- Supports faster recovery between efforts

- Helps maintain output consistency

From a clinical standpoint, this is highly relevant in clients who report:

- Feeling “flat” early in sessions

- Losing power quickly

- Needing longer recovery between efforts

- Cognitive fatigue alongside physical fatigue

Creatine can reduce the perceived cost of effort, particularly in repeated or intermittent tasks.

Creatine Is Not Just About Muscle

While creatine is best known for its role in muscle energetics, its relevance extends to other systems.

Neurological energy support

Creatine contributes to ATP buffering in neurons and glial cells, supporting:

- Neurotransmission

- Cognitive endurance

- Stress tolerance

This is why creatine is increasingly explored in contexts such as:

- Sleep deprivation

- Mood disorders

- Neurodegenerative conditions

(Though clinical use here requires careful scope and evidence alignment.)

Mitochondrial interaction

Creatine does not act inside the mitochondria, but it supports mitochondrial output indirectly by:

- Reducing demand pressure during rapid ATP turnover

- Allowing oxidative systems to “catch up”

- Improving overall energetic efficiency

This makes creatine complementary, not competitive with aerobic metabolism.

Reframing Creatine for Practice

For practitioners, the most important shift is moving away from the question:

“Is creatine useful for this client?”

…and instead asking:

“Does this client struggle with energy buffering, recovery, or repeated demand?”

When framed this way, creatine becomes relevant in conversations about:

- Fatigue and burnout

- Training tolerance

- Recovery quality

- Strength preservation

- Cognitive load

- Age-related decline

It is not a first-line intervention for every client, but neither is it niche.

Practical Considerations (Not Prescriptive)

From a practitioner perspective:

- Creatine monohydrate remains the most researched and cost-effective form

- Typical dosing strategies focus on low, consistent intake rather than loading

- Hydration status and gastrointestinal tolerance matter

- Creatine works best as part of a broader energy and recovery strategy, not in isolation

Importantly, creatine is not about forcing output. It’s about supporting capacity.

Creatine as an Energy Resilience Tool

Creatine’s reputation has been shaped by gym culture, but its biology tells a different story.

At its core, creatine:

- Protects ATP availability

- Buffers energetic stress

- Supports recovery between demands

- Contributes to physical and cognitive resilience

For practitioners working with fatigue, ageing, recovery, or performance in athletes or everyday clients, creatine deserves a more nuanced place in the conversation. Not as a “muscle supplement”, but as a foundational energy system support.

And that perspective changes how, when, and why we use it.

FREE RESOURCE